. . . is now called CD ROUNDUP.

Because my desk looks like this:

First installment coming soon.

One album, no scotch, one beer.

. . . is now called CD ROUNDUP.

Because my desk looks like this:

First installment coming soon.

Words: Vincent Abbate

Looking back in pop music history, you’ll find certain voices that were made for one another. Think about it: What would “Cathy’s Clown” have sounded like if it had only been Phil and not Phil and Don Everly on vocals? Would “The Sound of Silence” have been as powerful if Paul Simon or Art Garfunkel had sung it alone?

Like the aforementioned musical giants, songbird Emily Kelly has a voice that is lovely in its own right. Fellow Scot Graham Coe can more than carry a tune. Put them together and magic happens. In fact, Coe and Kelly possess an extremely rare ability to make their two voices move as one. That dynamic, more than anything else, is what makes Edinburgh-based acoustic duo The Jellyman’s Daughter such a captivating listen.

A few days ago I was preparing to interview Christian Rannenberg, one of the world’s finest blues piano players, for the Talkin’ Blues show in Cologne. Chris lives in Berlin and I hadn’t seen him for a number of years. So I did some digging to find out what he’d been up to. My most pleasant discovery was The Walter Davis Project.

Chris had told me about his intention to do a Walter Davis tribute album as far back as 2006. He’s been an admirer of Davis – the Mississippi-born pianist who recorded roughly 150 sides for the Victor and Bluebird labels in the 30s, 40s and 50s – ever since first sitting down to play the blues on a piano keyboard. As the initiator and driving force behind the project, he wound up investing a good deal of his own money on sessions with Billy Boy Arnold, Charlie Musselwhite and several others. But the recordings lay around gathering dust until Rannenberg and harmonica player Bob Corritore crossed paths at a memorial celebration for mutual friend Louisiana Red in 2012.

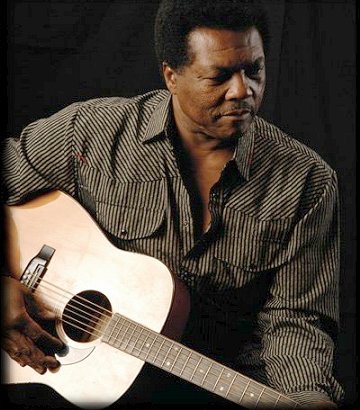

Terry Evans, who passed away on January 20th at the age of 80, had one of those phone book voices. You know: Open to any page in the phone book, hand it to Terry, have him sing it and wait for the goose bumps to come.

He was almost 70 years old when we spoke in 2005, coinciding with the release of his Fire In The Feeling album. At the time, he felt the voice he considered to be God-given growing gradually weaker.

“It’s not as strong now as it was 20 years ago,” said the man who’s first success came in the 1960s, backing singer Jewel Akens as a member of The Turnarounds. “Through experience, I know how to use my voice. But there are notes I can’t hit anymore that I used to hit effortlessly. Now it’s an effort.”

Time to kickstart a new year at Who Is Blues and to do some looking back forward.

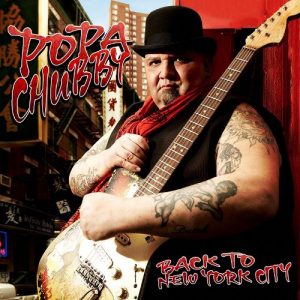

Picture me craning my neck from my birthplace on the south shore of Long Island to catch a glimpse of big city life in Manhattan. I didn’t much like the blandness of the suburbs growing up, so I made the move at 18, getting to know the heart of The Beast intimately during the drab, depressed, rodent-infested 1980s.

At the same time, Bronx native Ted Horowitz (aka Popa Chubby) was making a name for himself as a singer and guitarist at gloriously rowdy places like Dan Lynch’s Blues Bar on Second Avenue and 14th Street and Manny’s Car Wash up on Third Avenue and 88th Street. Chubby hosted a blues jam there before launching into a recording career that has seen him release roughly two dozen albums since the early 90s.

“They were inseparable, and they played together like brothers, sensing each other’s musical twists and turns before they happened, feeding energy and good spirits from one to the other.”

Thus wrote Bruce Iglauer of Alligator Records of singer/guitarist Theodore Roosevelt “Hound Dog” Taylor, guitarist Brewer Phillips and drummer Ted Harvey – the band of brothers who inspired him to start a record label.

“They fought like brothers too,” recalled Iglauer in 1982, “as they crisscrossed the country from gig to gig in Hound Dog’s old Ford station wagon, arguing constantly about who was the best lover, who had the best woman, who was the best mayor Chicago ever had, who was or wasn’t out of tune the night before. The arguments weren’t always in fun, either. From time to time a knife appeared, and finally even a gun.”

The dreary wet weather this morning has me thinking about rain songs. “Backwater Blues.” “Didn’t It Rain.” “When The Levee Breaks.” Flood songs.

There have been more than a few in the blues. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which took the lives of 246 people in seven states, is said to have inspired “When The Levee Breaks,” recorded by Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe two years later. It may also have provided the backdrop for John Lee Hooker’s “Tupelo Blues.” Hooker would have been about 10 years old at the time. Old enough to remember. Some sources say he was recalling another catastrophic Mississippi flood in 1936.

When autumn comes, the days get gloomier, the rain starts falling, I get to needing music more than in the sun-blessed days of spring and summer. Music like Doyle Bramhall II’s Rich Man.

Rich Man was among my favorites records of 2016 and is definitely one that feeds the soul. Two songs stand out for me. “November” is a beautifully-rendered remembrance of times spent with his musician father, Doyle Bramhall, who I was lucky enough to interview a few years before he passed in 2011. “New Faith” – sung as a duet with Norah Jones on the album – is illuminated from within by humanity and hope.

Doug MacLeod, one of today’s foremost specialists for bottleneck blues and fingerstyle guitar, has displayed his mastery of the craft on literally dozens of worthy compositions during the past 30 some-odd years. On rare occasions, the New York-born, St. Louis-bred, Southern California-based singer and storyteller plays with a full band behind him. More often, he chooses the minimal backing of drums and bass or sometimes just bass. And then there are the times he’ll play all by his lonesome … and you can’t believe it’s only him you’re hearing.

The river. It’s an often used symbol in rock’n’roll, blues, music in general. For a songwriter, the river’s mutability might suggest the fleetingness of life itself. But the river bank can also be a place of renewal, of baptism, of cleansing.

JJ Grey wrote “This River” after wandering down to the St. John’s River in his hometown of Jacksonville, Florida. The song closes the 2013 album of the same name, the sixth by Grey’s enduring southern soul, funk and blues project JJ Grey & Mofro.

Setting off with a lonesome acoustic guitar intro, carried along by a spare accompaniment of bass, drums and piano, with horns helping the song crescendo to a close, it is, above all, a showcase for Grey’s stark and powerful voice, which manages to communicate sorrow, remorse, resolve and contrition over the course of a gripping five-plus minutes. Continue reading